My

group’s approach to “Across Archives ‘n Ngrams” could be compared to a camera’s

focus options. While the purpose of the assignment was to consider patterns using our chosen terms (to zoom out and examine terms across texts and over time), we

honed in on the details of those terms. We focused carefully on the individual

instances and patterns presented in the archival tools themselves, noting the local inconsistencies and surprises they

revealed. We recognize that our close and deliberate analysis needed to take a big step backward.

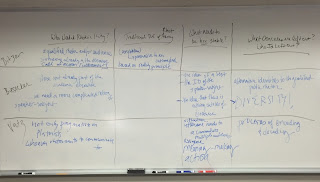

To look at this:

In the larger scheme of this:

(what do those little orange locations tell us about the term in this text and in the others?)

To respond to Dr. Graban’s prompt, the

archival tools addressed and illumined my understanding of the texts. My post

will consider the use of perception and language, both as the basis for Locke’s

theory of understanding and as guiding terms for Campbell’s “The Philosophy of

Rhetoric.”